How to leverage your intuition and make decisions

(even when the data isn’t clear)

I work with a lot of data-driven organizations.

Whether it’s finance geeks, business owners, software developers, or engineers, a lot of people who connect with my work self-identify as “data-driven.”

Don’t get me wrong, using data to make decisions is fantastic.

But, sometimes, it’s not enough.

At times, you may just need more data. You need to run an experiment longer, run a bigger survey, or just look more deeply at the data that you already have.

But, other times, you need a different approach; you need to break out of analysis paralysis.

Here are three approaches that you can use to make better decisions, even when embedded in a culture that celebrates data.

Broaden your perspective

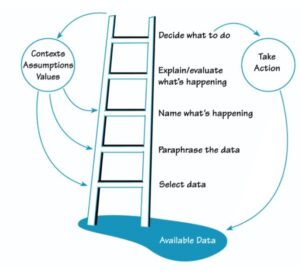

I wrote recently about Chris Argyris’s ladder of inference. The ladder is a mental model of how we process data and make decisions. Its key power is helping us become aware of the way that we unconsciously filter and interpret data that we all make.

What we measure becomes the water in which we swim.

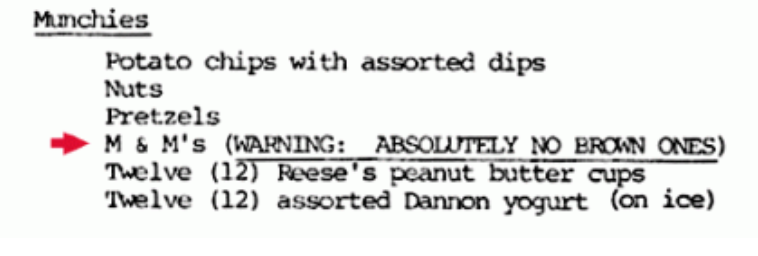

That’s OK — but the water often has a current that implies preexisting compromises. For example, an engineering manager at a tech firm might be incentivized to have her team close bug tickets swiftly. Open tickets may draw the attention (and ire?) of more senior leaders.

All of that influences her behavior in a particular way. If a deeper dive into a section of code would forestall future problems but would leave a ticket open longer, then an engineer may not be incentivized to make that investment — even if it would be good for the long-term health of the software.

In cases like this, using intuition and conversation to think through example problems can help us rethink our approaches. It can help us broaden what we measure and see more clearly what’s in front of us.

Realize that “the map is not the territory”

I’ve written here about how the environment we operate in changes whether intuition is a source of bias or a superpower to make great decisions. In an environment with a lot of feedback, we can learn from our decisions and improve our intuition.

Even in the most data-driven cultures, the map is not the territory. Data can never faithfully or fully represent the world as it is, whether that is because of the way that informal networks promote technology adoption or because work actually gets done in a different way than what’s written out as a procedure. That means that as data-driven as a culture is, data can’t be the only input for data.

As a result, many data-driven cultures struggle to incorporate intuitive solutions, even when they’re developed by experienced people drawing on their broad perspectives.

In these cases, rather than stake out and advocate a position, use intellectual judo to design an experiment:

I think we’d get newer developers up to speed faster if we paired them with formal mentors. Can we try an experiment where we do that for half of our starting developers and measure how much they deploy in the first three months?

These kinds of techniques work particularly well in big companies where you can benchmark internally. If you don’t have that option, you can still define smaller experiments where you predict specific outcomes and reflect on if you met your expectations.

Use HPPOs judiciously

When data fails, the default way of making decisions often follows the HPPO approach — to rely on the highest-paid person’s opinion.

That can be OK — sometimes a leader really does need to just make a decision. But groups often implicitly slide into this strategy. People might share their views, but subtly shape their input to match what they think a leader wants to hear.

That’s a mistake.

Instead, when you’re going to fall back on the highest-paid person’s opinion, make that explicit! A leader should proactively seek input while letting everyone know that she will ultimately be making the call. In this way, you can invite constructive dissent and empower everyone in the group to contribute.

That’s particularly useful when the data don’t show a clear path forward.

What about you? What approaches do you use to avoid analysis paralysis and make decisions, even when the data aren’t clear?